申命記

|

または

|

|---|

詳細は聖書正典を参照

|

ユダヤ教とプロテスタントが除外

|

東方正教会が含む

|

エチオピア正教会が含む

|

ペシッタ訳聖書が含む

|

目次

[非表示]

|

名称 [編集]

内容 [編集]

- 第1の説話(1章~4章)では、40年にわたる荒れ野の旅をふりかえり、神への忠実を説く。

- 第2の説話(5章~26章)は中心部分をなし、前半の5章から11章で十戒が繰り返し教えられ、後半の12章から26章で律法が与えられている。

- 最後の説話(27章~30章)では、神と律法への従順、神とイスラエルの契約の確認、従順なものへの報いと不従順なものへの罰が言及される。

- 最後の説話の後、モーセは来るべき死への準備をし、ヨシュアを自らの後継者として任命する。その後、補遺といわれる部分が続く。

- 32章1節~47節は、『モーセの歌』といわれるものである。

- 33章では、モーセがイスラエルの各部族に祝福を与える。

- 32章48節~52節および34章では、モーセの死と埋葬が描かれて、モーセ五書の幕が閉じられる。

著者の問題 [編集]

伝統的解釈 [編集]

古代以来、伝承ではモーセ五書はすべてモーセが書いたとされていた。タルムードは初めてモーセがモーセ五書のすべてを書いたという伝承に関する議論を提起した。考えればわかることだが、どうやってモーセが自らの死を記述しえたのかという疑問が示されたのである。あるラビはモーセが自らの死と埋葬を予言的に記述したという見解を述べたが、多くのラビたちはモーセの死と埋葬に関する部分のみヨシュアが書いたということでこの疑問への答えとした。

中世の解釈 [編集]

中世に入ると12世紀のユダヤ人聖書学者アブラハム・イブン・エズラがモーセ五書に関する初の学術的研究を行って、『申命記』は記述のスタイルや語法が他の四書と異なっていることに気づいた。彼は古代以来の伝承に従っておそらくスタイルの違いはモーセとヨシュアの違いによるものだろうと考えたが、15世紀のドン・アイサック・アブラヴァネルは『申命記詳解』の序文で申命記のみ他の四書と違う(ヨシュアでもない)別個の著者の手によるものという見解を示した。

近代自由主義の解釈 [編集]

近代に入って旧約聖書とイスラエルの歴史に関する学術的な研究がすすむと『列王記下』の終盤と『歴代誌』34章であらわれヨシヤ王治下での宗教改革と『申命記』を結びつける説が18世紀初頭W・M・L・デ・ヴェッテにより初めて唱えられた。[1]その部分の記述によれば紀元前621年、ヨシヤ王は聖所から偶像崇拝や異教の影響を排除した。その過程で大祭司ヒルキヤの手によって律法の失われた書物が発見されたというのである。ヒルキヤはヨシヤ王にこの書物を見せ、2人は女預言者フルダにこれが失われた律法の書であることの確認を求めた。フルダがこれこそが本来の律法であると告げたため、王は民衆の前でこの書を読み上げて、神と民の契約の更新を確認し、以後の儀式がこの書にもとづいて行われるむねを告げた。タルムードの中のラビたちの伝承と同じく、近代の研究者たちもこの「失われた書物」は『申命記』に他ならないと考えた。『申命記』はモーセ五書の中で唯一、「ただひとつの聖所」の重要性を訴えている。当時、多くの場所にあった聖所を一箇所にまとめること、それによって王権を強化することがヨシヤ王の改革の狙いだったのではないかと考えられたのである。このことからヨシヤの改革を「申命記改革」と呼ぶ。

現代の保守的解釈 [編集]

脚注 [編集]

- ^ 後藤茂光「申命記」661ページ(『新聖書辞典』)いのちのことば社、1985年

- ^ 後藤茂光「申命記」,661ページ『新聖書辞典』,いのちのことば社

- ^ K・A・キッチン著、津村俊夫訳『古代オリエントと旧約聖書』いのちのことば社、1979年、170ページ

関連項目 [編集]

| |||||||||||

Book of Deuteronomy

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Tanakh and

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

|

| ||

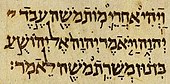

The Book of Deuteronomy

(from Greek Δευτερονόμιον,

Deuteronomion,"second law";

Hebrew: דְּבָרִים, Devarim,

"[spoken] words")

is the fifth book of the Heb-rew Bible, and of the Jewish Torah/ Pentate-uch.

The Hebrew title is taken from the opening phraseEleh ha-devarim, "These are the words..."; the English title is from a Greek mis-translation of the Hebrew phrase mishneh ha-torah ha-zoth, "a copy of this law", in Deuteronomy 17:18, as to deuterono-mion touto - "this second law".[1]

(from Greek Δευτερονόμιον,

Deuteronomion,"second law";

Hebrew: דְּבָרִים, Devarim,

"[spoken] words")

is the fifth book of the Heb-rew Bible, and of the Jewish Torah/ Pentate-uch.

The Hebrew title is taken from the opening phraseEleh ha-devarim, "These are the words..."; the English title is from a Greek mis-translation of the Hebrew phrase mishneh ha-torah ha-zoth, "a copy of this law", in Deuteronomy 17:18, as to deuterono-mion touto - "this second law".[1]

The book consists of three sermons or speech-es delivered to theIsraelites by Moses on the plains of Moab, shortly before they enter thePromised Land.

The first sermon recapitulates the forty years of wilderness wanderings which have led to this moment, and ends with an exhortation to observe the law (or teachings); the second reminds the Israelites of the need for exclu-sive allegiance to one God and observance of the laws he has given them, on which their possession of the land depends; and the third offers the comfort that even should Israel prove unfaithful and so lose the land, with repentance all can be restored.[2]

The first sermon recapitulates the forty years of wilderness wanderings which have led to this moment, and ends with an exhortation to observe the law (or teachings); the second reminds the Israelites of the need for exclu-sive allegiance to one God and observance of the laws he has given them, on which their possession of the land depends; and the third offers the comfort that even should Israel prove unfaithful and so lose the land, with repentance all can be restored.[2]

Traditionally accepted as the genuine words of Moses delivered on the eve of the occupa-tion of Canaan, a broad consensus of modern scholars see its origins in traditions from Israel (the northern kingdom) brought south to the Kingdom of Judah in the wake of the Assyrian destruction of Samaria (8th century BCE) and then adapted to a program of natio-nalist reform in the time of King Josiah (late 7th century), with the final form of the modern book emerging in the milieu of the return from the Babylonian exile during the late 6th century.[3]

One of its most significant verses is Deuteronomy 6:4, the Shema, which has become the definitive statement of Jewish identity: "Hear, O Israel: the LORD our God, the LORD is one." Verses 6:4-5 were also quoted by Jesus in Mark 12:28-34 as part of the Great Commandment.

Contents

[hide]

|

[edit]Contents

- For detailed contents see:

- Devarim, on Deuteronomy 1-3: Chiefs, scouts, Edom, Ammonites, Sihon, Og, land for two and a half tribes

- Va'etchanan, on Deuteronomy 3-7: Cities of refuge, Ten Commandments, exhortation, conquest instructions

- Eikev, on Deuteronomy 7-11: Obedience, taking the land, golden calf, Aaron’s death, Levites’ duties

- Re'eh, on Deuteronomy 11-16: Centralized worship, diet, tithes, sabbatical year, pilgrim festivals

- Shoftim, on Deuteronomy 16-21: Basic societal structure for the Israelites

- Ki Teitzei, on Deuteronomy 21-25: Miscellaneous laws on civil and domestic life

- Ki Tavo, on Deuteronomy 26-29: First fruits, tithes, blessings and curses, exhortation

- Nitzavim, on Deuteronomy 29-30: covenant, violation, choose blessing and curse

- Vayelech, on Deuteronomy 31: Encouragement, reading and writing the law

- Haazinu, on Deuteronomy 32: Punishment, punishment restrained, parting words

- V'Zot HaBerachah, on Deuteronomy 33-34: Farewell blessing and death of Moses

[edit]Structure

Patrick D. Miller in his commentary on Deuteronomy suggests that different views of the structure of the book will lead to different views on what it is about.[5] The structure is often described as a series of three speeches or sermons (chapters 1:1-4:43, 4:44-29:1, 29:2-30:20) followed by a number of short appendices[6] – Miller refers to this as the "literary" structure; alternatively, it is sometimes seen as a ring-structure with a central core (chapters 12-26, the Deuteronomic code) and an inner and an outer frame (chapters 4-11/27-30 and 1-3/31-34)[6] – Miller calls this the covenantal substructure;[5] and finally the theological structure revealed in the theme of the exclusive worship of Yahweh established in the first of the Ten Commandments ("Thou shalt have no other god before me") and the shema ("Hear O Israel, the LORD our God is One!")[5]

[edit]Summary

(The following "literary" outline of Deuteronomy is from John Van Seters;[7] it can be contrasted with Alexander Rofé's "covenantal" analysis in his Deuteronomy: Issues and Interpretation.[8])

- Chapters 1-4: The journey through the wilderness from Horeb (Sinai) to Kadesh and then to Moab is recalled.

- Chapters 4-11: After a second introduction at 4:44-49 the events at Mount Horeb (Mt. Sinai) are recalled, with the giving of the Ten Commandments. Heads of families are urged to instruct those under their care in the law, warnings are made against serving gods other than Yahweh, the land promised to Israel is praised, and the people are urged to obedience.

- Chapters 12-26, the Deuteronomic code: Laws governing Israel's worship (chapters 12-16a), the appointment and regulation of community and religious leaders (16b-18), social regulation (19-25), and confession of identity and loyalty (26).

- Chapters 27-28: Blessings and curses for those who keep and break the law.

- Chapters 29-30: Concluding discourse on the covenant in the land of Moab, including all the laws in the Deuteronomic code (chapters 12-26) after those given at Horeb; Israel is again exhorted to obedience.

- Chapters 31-34: Joshua is installed as Moses' successor, Moses delivers the law to the Levites (priests), and ascends Mount Nebo/Pisgah, where he dies and is buried by God. The narrative of these events is interrupted by two poems, the Song of Moses and the Blessing of Moses.

The final verses, Deuteronomy 34:10-12, "never again did there arise in Israel a prophet like Moses," state authoritatively that the Deuteronomistic view of theology, with its insistence on the worship of Yahweh as the sole God of Israel, was the only permissible religion, sealed by the greatest of prophets.[9]

[edit]Deuteronomic code

Main article: Deuteronomic Code

Deuteronomy 12-26, the Deuteronomic Code, is its oldest part of the book and the core around which the rest developed.[10] It is a series of mitzvot (commands) to the Israelites regarding how they ought to conduct themselves in Canaan, the land promised by Yahweh, God of Israel. The laws include (listed here in no particular order):

- The worship of God must remain pure, uninfluenced by neighbouring cultures and their idolatrous religious practices. The death penalty is prescribed for conversion from Yahwism and for proselytisation.

- The death penalty is also prescribed for males who are guilty of disobeying their parents, profligacy, ordrunkenness.

- Certain Dietary principles are enjoined.

- The law of rape prescribes various conditions and penalties, depending on whether the girl is engaged to be married or not, and whether the rape occurs in a town or in the country. (Deuteronomy 22)

- A Tithe for the Levites and charity for the poor.

- A regular Jubilee Year during which all debts are cancelled.

- Slavery can last no more than 6 years if the individual purchased is "thy brother, an Hebrew man, or an Hebrew woman."

- Yahwistic religious festivals—including Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot—are to be part of Israel's worship

- The offices of Judge, King, Kohen (temple priest), and Prophet are instituted

- A ban against worshipping Asherah next to altars dedicated to Yahweh, and the erection of sacred stones

- A ban against children either being immolated or passing through fire (the text is ambiguous as to which is meant), divination, sorcery, witchcraft, spellcasting, and necromancy

- A ban forbidding blemished animals from becoming sacrifices at the Temple

- Naming of three cities of refuge where those accused of manslaughter may flee from the avenger of blood.

- Exemptions from military service for the newly betrothed, newly married, owners of new houses, planters of new vineyards, and anyone afraid of fighting.

- The peace terms to be offered to non-Israelites before battle - the terms being that they are to become slaves

- The Amalekites to be utterly destroyed

- An order for parents to take a stubborn and rebellious son before the town elders to be stoned.

- A ban on the destruction of fruit trees, the mothers of newly-born birds, and beasts of burden which have fallen over or are lost

- Rules which regulate marriage, and Levirate Marriage, and allow divorce.

- The procedure to be followed if a man suspects that his new wife is not a virgin: if the wife's parents are able to prove that she was indeed a virgin then the man is fined; otherwise the wife is stoned to death.[11]

- Purity laws which prohibit the mixing of fabrics, of crops, and of beasts of burden under the same yoke.

- The use of Tzitzit (tassels on garments)

- Prohibition against people who are of illegitimate birth, and even their descendants to the tenth generation, from entering the house of the lord; the same restriction upon those who are castrated (but not their descendants)

- Regulations for ritual cleanliness, general hygiene, and the treatment of Tzaraath

- A ban on religious prostitution

- Regulations for slavery, servitude, vows, debt, usury, and permissible objects for securing loans

- Prohibition against wives making a groin attack on their husband's adversary.

- Regulations on the taking of wives from among beautiful female captives.[12]

- A ban on transvestism.[13]

- Regulations on military camps, including a cleanliness regime for soldiers who have had wet dreams and procedures for the burial of human excrement.[14]

[edit]Composition

[edit]Composition history

Since the evidence was first put forward by W.M.L de Wette in 1805, scholars have accepted that the core of Deuteronomy was composed in Jerusalem in the 7th century BCE in the context of religi-ous reforms advanced by King Josiah (reigned 641-609 BCE). -15]

A broad consensus exists that sees its history in the fo-llowing general terms:[3]

- In the late 8th century both Judah and Israel were vassals ofAssyria.

- Israel rebelled, and was destroyed c.722 BCE. Refugees fleeing to Judah brought with them a number of new traditions (new to Judah, at least). One of these was that the god Yahweh, already known and worship-ed in Judah, was not merely the most important of the gods, but the only god who should be served.

- This outlook influenced the Judahite landowning elite, who became extremely powerful in court circles after they placed the eight year old Josiah on the throne following the murder of his father.

- By the eighteenth year of Josiah's reign, Assyrian power was in rapid decline, and a pro-independence movement gathered streng-th in the court.

- This movement expressed itself in a state theology of loyalty to Yahweh as the sole god of Israel. With Josiah's support they launched a full-scale reform of worship based on an early form of Deuteronomy 5-26, which takes the form of a covenant (i.e., treaty) between Judah and Yahweh to replace that between Judah and Assyria.

- This covenant was formulated as an address by Moses to the Israelites (Deut.5:1).

- The next stage took place during the Babylonian exile. The destruction of Judah by Babylon in 586 BCE and the end of king-ship was the occasion of much reflection and theological speculation among the Deuteronomistic elite, now in exile in Babylon.

- They explained the disaster as Yahweh's punishment of their failure to follow the law, and created a history of Israel (the books of Joshua through Kings) to illustrate this.

- At the end of the Exile, when the Persians agreed that the Jews could return and rebuild the Temple, chapters 1-4 and 29-30 were added and Deuteronomy was made the introductory book to this history, so that a story about a people about to enter the Promised Land, became a story about a people about to return to the land.

- The legal sections of chapters 19-25 were expanded to meet new situations that had arisen, and chapters 31-34 were added as a new conclusion.

[edit]Sources

The prophet Isaiah, active in Jerusalem about a century before Josiah, makes no mention of the Exodus, covenants with God, or disobedi-ence to God's laws; in contrast Isaiah's con-temporary Hosea, active in the northern king-dom of Israel, makes frequent reference to the Exodus, the wilderness wanderings,

a covenant, the danger of foreign gods and the need to worship Yahweh alone; this has led scholars to the view that these tradi-tions behind Deuteronomy have a northern origin.[16]

Whether the Deuteronomic code – the set of laws at chapters 12-26 which form the ori-ginal core of the book – was written in Josiah's time (late 7th century) or earlier is subject to debate, but many of the indi-vidual laws are older than the collection itself.[17]

The two poems at chapters 32-33 – the Song of Moses and the Blessing of Moses were probably originally independent.[16]

a covenant, the danger of foreign gods and the need to worship Yahweh alone; this has led scholars to the view that these tradi-tions behind Deuteronomy have a northern origin.[16]

Whether the Deuteronomic code – the set of laws at chapters 12-26 which form the ori-ginal core of the book – was written in Josiah's time (late 7th century) or earlier is subject to debate, but many of the indi-vidual laws are older than the collection itself.[17]

The two poems at chapters 32-33 – the Song of Moses and the Blessing of Moses were probably originally independent.[16]

[edit]Position in the Hebrew Bible

Deuteronomy occupies a puzzling position in the Bible, linking the story of the Israe-lites' wanderings in the wilderness to the story of their history in Canaan without quite belonging totally to either.

The wilderness story could end quite easily with Numbers, and the story of Joshua's conquests could exist without it, at least at the level of the plot; but in both cases there would be a thematic (theological) element missing.

Scholars have given various answers to the problem. The Deuteronomistic history theory is currently the most popular (Deuteronomy was originally just the law code and cove-nant, written to cement the religious reforms of Josiah, and later expanded to stand as the introduction to the full history); but there is an older theory which sees Deuteronomy as belonging to Numbers, and Joshua as a sort of supplement to it.

This idea still has supporters, but the main-stream understanding is that Deuteronomy, after becoming the introduction to the his-tory, was later detached from it and included with Genesis-Exodus-Leviticus-Numbers because it already had Moses as its central chara-cter. According to this hypothesis, the death of Moses was originally the ending of Num-bers, and was simply moved from there to the end of Deuteronomy.[18]

The wilderness story could end quite easily with Numbers, and the story of Joshua's conquests could exist without it, at least at the level of the plot; but in both cases there would be a thematic (theological) element missing.

Scholars have given various answers to the problem. The Deuteronomistic history theory is currently the most popular (Deuteronomy was originally just the law code and cove-nant, written to cement the religious reforms of Josiah, and later expanded to stand as the introduction to the full history); but there is an older theory which sees Deuteronomy as belonging to Numbers, and Joshua as a sort of supplement to it.

This idea still has supporters, but the main-stream understanding is that Deuteronomy, after becoming the introduction to the his-tory, was later detached from it and included with Genesis-Exodus-Leviticus-Numbers because it already had Moses as its central chara-cter. According to this hypothesis, the death of Moses was originally the ending of Num-bers, and was simply moved from there to the end of Deuteronomy.[18]

[edit]Themes

[edit]Overview

Deuteronomy stresses the uniqueness of God, the need for drastic centralisation of wor-ship, and a concern for the position of the poor and disadvantaged.[19]

Its many themes can be organised around the three poles of Israel, Israel's god, and the covenant which binds them together.

Additionally, it stresses the importance of harsh laws and being put to the death for the smallest of transgressions.

Its many themes can be organised around the three poles of Israel, Israel's god, and the covenant which binds them together.

Additionally, it stresses the importance of harsh laws and being put to the death for the smallest of transgressions.

[edit]Israel

The themes of Deuteronomy in relation to Israel are election, faithfulness, obedience, and God's promise of blessings, all expressed through the covenant:

"obedience is not primarily a duty imposed by one party on another, but an expression of covenantal relationship."[20]

Yahweh has chosen ("elected") Israel as his special property (Deuteronomy 7:6 and elsewhere),[21] and Moses stresses to the Israelites the need for obedience to God and covenant, and the consequences of unfaithfulness and disobedience.[22]

Yet the first several chapters of Deuteronomy are a long retelling of Israel's past dis-obedience - but also God's gracious care, leading to a long call to Israel to choose life over death and blessing over curse (chapters 7-11).

"obedience is not primarily a duty imposed by one party on another, but an expression of covenantal relationship."[20]

Yahweh has chosen ("elected") Israel as his special property (Deuteronomy 7:6 and elsewhere),[21] and Moses stresses to the Israelites the need for obedience to God and covenant, and the consequences of unfaithfulness and disobedience.[22]

Yet the first several chapters of Deuteronomy are a long retelling of Israel's past dis-obedience - but also God's gracious care, leading to a long call to Israel to choose life over death and blessing over curse (chapters 7-11).

[edit]God

Deuteronomy's concept of God changed over time:

the earliest 7th century layer is monolatrous, not denying the reality of other gods but enforcing the worship of Yahweh in Jerusalem alone; in the later, Exilic layers from the mid-6th century, especially chapter 4, this becomes monotheism, the idea that only one god exists.[25]

After the review of Israel's history in chapters 1 to 4, there is a restatement of the Decalogue in chapter 5.

This arrangement of material highlights God's sovereign relationship with Israel prior to the giving of establishment of the Law.[27]

The Decalogue in turn then provides the foundational principles for the subsequent, more detailed laws. Some scholars go so far as to see a correlation between each of the laws of the Decalogue and each of the more detailed 'case-law' of the rest of the book.[28]

This foundational aspect of the Decalogue is also demonstrated by the emphasis to actively remember the law of God (Deuteronomy 6:4–9), immediately after the Decalogue. The Law as it is broadly presented across Deuteronomy defines Israel both as a community and defines their relationship with Yahweh.

There is throughout the law a sense of justi-ce.

For example the demand for multiple witness (Deuteronomy 17:6–7), cities of refuge (19:1–10), or the provision of judges (17:8–13).

This arrangement of material highlights God's sovereign relationship with Israel prior to the giving of establishment of the Law.[27]

The Decalogue in turn then provides the foundational principles for the subsequent, more detailed laws. Some scholars go so far as to see a correlation between each of the laws of the Decalogue and each of the more detailed 'case-law' of the rest of the book.[28]

This foundational aspect of the Decalogue is also demonstrated by the emphasis to actively remember the law of God (Deuteronomy 6:4–9), immediately after the Decalogue. The Law as it is broadly presented across Deuteronomy defines Israel both as a community and defines their relationship with Yahweh.

There is throughout the law a sense of justi-ce.

For example the demand for multiple witness (Deuteronomy 17:6–7), cities of refuge (19:1–10), or the provision of judges (17:8–13).

[edit]Covenant

The core of Deuteronomy is the Biblical covenant which binds Yahweh and Israel by oaths of fidelity (Yahweh and Israel each faithful to the other) and obedience (Israel obedient to Yahweh).[29]

God will give Israel blessings of the land,

But, according to the Deuteronomists, Israel's prime sin is lack of faith, apos-tacy:

God will give Israel blessings of the land,

fertility, and prosperity so long as Israel is faithful to God's teaching; disobedience will lead to curses and punishment.[30]

But, according to the Deuteronomists, Israel's prime sin is lack of faith, apos-tacy:

contrary to the first and fundamental commandment ("Thou shalt have no other gods before me") the people have entered into relations with other gods.[31]

The covenant is based on 7th century Assyrian suzerain-vassal treaties by which the Great King (the Assyrian suzerain) regulated relationships with lesser rulers; Deuteronomy is thus making the claim that Yahweh, not the Assyrian monarch, is the Great King to whom Israel owes loyalty.[32]

The terms of the treaty are that Israel holds the land from Yahweh,

The terms of the treaty are that Israel holds the land from Yahweh,

but Israel's tenancy of the land is conditional on keeping the cove-nant, which in turn necessitates tempered rule by state and village leaders who keep the covenant:

Dillard and Longman in their Introduction to the Old Testament stress the living nature of the covenant between Yahweh and Israel as a nation: The people of Israel are addressed by Moses as a unity, and their allegiance to the covenant is not one of obeisance, but comes out of a pre-existing relationship between God and Israel, established with Abraham and attested to by the Exodus event, so that the laws of Deuteronomy set the nation of Israel apart, signaling the unique status of the Jewish nation.[34]

The land is God's gift to Israel, and many of the laws, festivals and instructions in Deuteronomy are given in the light of Israel's occupation of the land. Dillard and Longman note that "In 131 of the 167 times the verb "give" occurs in the book, the subject of the action is Yahweh."[35]

Deuteronomy makes the Torah the ultimate authority for Israel, one to which even the king is subject.[36]

The land is God's gift to Israel, and many of the laws, festivals and instructions in Deuteronomy are given in the light of Israel's occupation of the land. Dillard and Longman note that "In 131 of the 167 times the verb "give" occurs in the book, the subject of the action is Yahweh."[35]

Deuteronomy makes the Torah the ultimate authority for Israel, one to which even the king is subject.[36]

[edit]Influence on Judaism and Christianity

[edit]Judaism

Deuteronomy 6:4-5:

"Hear (shema), O Israel, the LORD is our God, the LORD is one!" has become the basic credo of Judaism, and its twice-daily recitation is a mitzvah (religious commandment).

The shema goes on: "Thou shalt love the LORD thy God with all thy heart and all thy soul and all thy might"; it has therefore also become identified with the central Jewish concept of the love of God, and the rewards that come with this.

"Hear (shema), O Israel, the LORD is our God, the LORD is one!" has become the basic credo of Judaism, and its twice-daily recitation is a mitzvah (religious commandment).

The shema goes on: "Thou shalt love the LORD thy God with all thy heart and all thy soul and all thy might"; it has therefore also become identified with the central Jewish concept of the love of God, and the rewards that come with this.

[edit]Christianity

In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus cited Deuteronomy 6:5 as a Great Commandment.

The earliest Christian authors interpreted Deuteronomy's prophecy of the restoration of Israel as having been fulfilled (orsuperse-ded)

The earliest Christian authors interpreted Deuteronomy's prophecy of the restoration of Israel as having been fulfilled (orsuperse-ded)

in Jesus Christ and the establishment of the Christian church (Luke 1-2, Acts 2-5), and Jesus was interpreted to be the "one (i.e., prophet) like me" predicted by Moses in Deuteronomy 18:15 (Acts 3:22-23).

In place of the elaborate code of laws ("torah") set out in Deuteronomy, St. Paul, drawing on Deuteronomy 30:11-14, claimed that the keeping of the Mosaic covenant was overturned by faith in Jesus and the gospel (the New Covenant).[37]

[edit]See also

- Deuteronomic Code

- Deuteronomist

- Deuteronomistic history

- Documentary hypothesis

- Kosher

- Mosaic authorship

- Tanakh

- Torah

- Weekly Torah portions in Deuteronomy: Devarim, Va'etchanan, Eikev, Re'eh, Shoftim, Ki Teitzei, Ki Tavo,Nitzavim, Vayelech, Haazinu, V'Zot HaBerachah.

- Papyrus Rylands 458 – the oldest Greek manuscript of Deuteronomy

[edit]References

- ^ Miller, pp.1-2

- ^ Phillips, pp.1-2

- ^ a b Rogerson, pp.153-154

- ^ Avigdor Miller (2001). Fortunate Nation:Comments and notes on DVARIM. p. 1.

- ^ a b c Miller, p.10

- ^ a b Christensen, p.211

- ^ Van Seters, pp.15-17

- ^ Rofé, pp.1-4

- ^ Tigay, pp.137ff.

- ^ Van Seters, p.16

- ^ Deut. 22:13-21

- ^ Deut. 21:10-14

- ^ Deut. 22:5

- ^ Deut. 23:10-14

- ^ Rofé, pp.4-5

- ^ a b Van Seters, p.17

- ^ Knight, p.66

- ^ Bandstra, pp.190-191

- ^ McConville

- ^ Block, p.172

- ^ McKenzie, p.266

- ^ Bultman, p.135

- ^ Millar, 'Deuteronomy', 161.

- ^ Dillard & Longman, p.104

- ^ Romer (1994), p.200-201

- ^ McKenzie, p.265

- ^ Thompson, Deuteronomy, 112.

- ^ Braulik (no page available)

- ^ Breuggemann, p.53

- ^ Laffey, p.337

- ^ Phillips, p.8

- ^ Vogt, p.28

- ^ Gottwald

- ^ Dillard & Longman, p.102.

- ^ Dillard & Longman, p.104.

- ^ Vogt, p.31

- ^ McConville, p.24

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]Translations of Deuteronomy

[edit]Commentaries on Deuteronomy

- Craigie, Peter C (1976). The Book of Deuteronomy. Eerdmans.

- Miller, Patrick D (1990). Deuteronomy. Cambridge University Press.

- Phillips, Anthony (1973). Deuteronomy. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Avigdor Miller (2001). Fortunate Nation:Comments and notes on DVARIM.

[edit]General

- Bandstra, Barry L (2004). Reading the Old Testament: an introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Wadsworth.

- Block, Daniel I (2005). "Deuteronomy". In Kevin J. Vanhoozer. Dictionary for Theological Interpretation of the Bible. Baker Academic.

- Braulik, G (1998). The Theology of Deuteronomy: Collected Essays of Georg Braulik. D&F Scott Publishing.

- Brueggemann, Walter (2002). Reverberations of faith: a theological handbook of Old Testament themes. Westminster John Knox.

- Bultman, Christoph (2001). "Deuteronomy". In John Barton, John Muddiman. Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press.

- Christensen, Duane L (1991). "Deuteronomy". In Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard. Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press.

- Dillard, Raymond B.; Longman, Tremper (January 1994) (PDF, 3.5 MB). An Introduction to the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-43250-0. LCCN 2006005249.OCLC 31046001. Retrieved 2012-02-24.

- Gottwald, Norman, review of Stephen L. Cook, The Social Roots of Biblical Yahwism, Society of Biblical Literature, 2004

- Knight, Douglas A (1995). "Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomists". In James Luther Mays, David L. Petersen, Kent Harold Richards. Old Testament Interpretation. T&T Clark.

- Laffey, Alice L (2007). "Deuteronomistic theology". In Orlando O. Espín, James B. Nickoloff. An introductory dictionary of theology and religious studies. Liturgical Press.

- McConville, J.G (2002). "Deuteronomy". In T. Desmond Alexander, David W. Baker. Dictionary of the Old Testament: The Pentateuch. Eisenbrauns.

- McKenzie, Steven L (1995). "Postscript". In Linda S. Schearing, Steven L McKenzie. Those elusive Deuteronomists: the phenomenon of Pan-Deuteronomism. T&T Clark.

- Richter, Sandra L (2002). The Deuteronomistic history and the name theology. Walter de Gruyter.

- Rofé, Alexander (2002). Deuteronomy: issues and interpretation. T&T Clark.

- Rogerson, John W (2003). "Deuteronomy". In James D. G. Dunn and John William Rogerson. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans.

- Romer, Thomas (2000). "Deuteronomy In Search of Origins". In Gary N. Knoppers, J. Gordon McConville. Reconsidering Israel and Judah: recent studies on the Deuteronomistic history. Eisenbrauns.

- Romer, Thomas (1994). "The Book of Deuteronomy". In Steven L. McKenzie, Matt Patrick Graham. The history of Israel's traditions: the heritage of Martin Noth. Sheffield Academic Press.

- Tigay, Jeffrey (1996). "The Significance of the End of Deuteronomy". In Michael V. Fox et. al. Texts, temples, and traditions: a tribute to Menahem Haran. Eisenbrauns.

- Van Seters, John (1998). "The Pentateuch". In Steven L. McKenzie, Matt Patrick Graham. The Hebrew Bible today: an introduction to critical issues. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Vogt, Peter T (2006). Deuteronomic theology and the significance of Torah: a reappraisal. Eisenbrauns.

[edit]External links

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

|

- Deuteronomy at Bible Gateway

James Alexander Paterson (1911). "Deuteronomy".Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

James Alexander Paterson (1911). "Deuteronomy".Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Morris Jastrow (1905). "Deuteronomy". New International Encyclopedia.

Morris Jastrow (1905). "Deuteronomy". New International Encyclopedia.

- Jewish translations:

- Deuteronomy at Mechon-Mamre (modified Jewish Publication Society translation)

- Deuteronomy (The Living Torah) Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan's translation and commentary at Ort.org

- Devarim – Deuteronomy (Judaica Press) translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- דְּבָרִים Devarim – Deuteronomy (Hebrew - English at Mechon-Mamre.org)

- Christian translations:

Book of Deuteronomy

| ||

Preceded by

|

Succeeded by

| |

| ||

No comments:

Post a Comment